大自然と人間を繋ぐ神々への想い ~木曽御嶽山~ 上編

山岳信仰の代表的な山として知られる御嶽山は、平成26年9月に突然の噴火により戦後最悪の火山災害の地となった――。まだ往時の活況には程遠いものの、この山が持つ神秘的な魅力は、多くの人々の心を引きつけている。

長野県と岐阜県の県境に位置し、古くから信仰の山として多くの人々の心象風景に深く刻まれてきた木曽御嶽山。平成26年の御嶽山噴火は戦後最悪の火山災害として、山好きに限らず、日本に住む人であれば知らない人はいないほど、我々に驚きと恐怖、そして悲しみをもたらせ、自然の驚異的な力をまざまざと見せつけることになった。みなさんの記憶の中にも鮮明に刻まれた出来事ではないだろうか。

平成31年の現在でさえ、突発的な火山灰などのごく小規模な噴出には最大限の注意が必要だ。入山が出来たとしても各自治体による立ち入り規制などがところどころに存在する。本来はどの山であろうと当たり前の話だが――、今後御嶽山各所の規制が緩和されたとしても、入山をする際には最大限の注意を払い、出来うる限りの準備をして大自然への畏怖の心のもとに足を踏み入れなければならない。

直近における痛ましい災害記憶の強く残るこの御山のことを、どのように紹介すべきかは大変に頭を悩ませた。多くの方にとってご存じの事ばかりかもしれないが、祈りの山であり山岳信仰の代表的な存在としての御嶽信仰について、また自身においても思いを馳せるシンボルである御嶽山そのものについて、火山災害から丸4年たつこのタイミングであえてここに記していきたいと考えた。

この記事をご覧いただいた読者の方で、今後もし御嶽山への登拝を検討されている方がいらっしゃった場合、くれぐれも前述の通りの意識のもとに、その山行に取り組んでいただきたいと心から願っている。

*

夏の木曽御嶽山に登ると、白装束に身を固めたたくさんの人々に出会う。これらの人々は御嶽山を信仰の対象とした「御嶽講」と呼ばれる集団が行う夏山登拝の参加者である。人々は先達(信仰の山における指導者的な役割のこと)の指導のもと、元気な子供も足腰が弱った高齢者も一体となり、助け合いながらゆっくりと着実に山頂を目指して歩を進めていく。

また、これらの人々は山中各地の拝所において、修験者(山伏)のように印を結び仏教の真言や経文を唱え、一方では神道の祝詞を唱え拍手を打ち、祈りをささげ、さらには山中の聖地や山頂において「御座(おざ)」と呼ばれる神おろしの儀礼をおこなっている。すべての講が同じというわけではないが、多くの「御嶽講」が神道の神と仏教の仏をともに大事にする神仏習合的な信仰を登拝や儀礼を通して伝えてきた。

しかし同じ山岳信仰の世界であっても、修験道の行者と「御嶽講」の先達や信徒には若干の違いが見て取れる。

そもそも修験道自体は、どの御山での修業なのかによって信仰形態は異なる。とはいえ多くの修験者たちはいかめしい装束に身を包み、山々を風のように駆け抜け、岩場をよじ登り、生と死の狭間を行き来することも修行として取り組んでいる。

それに比べ御嶽における先達や信徒は簡素な白装束を身に纏い、ゆっくりと講中(参加者)全員を山に引き上げるように登っていくことを常とする。こう考えると修験道と「御嶽講」は大変良く似た部分と異なる部分を持ち合わせていると言えよう。

似通う部分としては、ともに御山に生きる草花や木々、岩や川、風や雲など自然そのものと、その現象すべてに神仏の存在を見出し、「おつとめ」や「勤行」と呼ばれる参拝の際に唱えられる経文や真言、祝詞の奏上といった宗教儀式の行い方を挙げることができる。

一方で異なる点としては、例えば大峰奥駆け修行や羽黒山秋の峰入りなどに代表される山伏修行は、強い体力と機根が求められるやや専門的な修行であることから、誰もが気軽に参加できるものではない。しかし「御嶽講」の登拝の場合、希望するならば児童も高齢者も山に導こうとする大らかな抱擁性が強く、大袈裟に言えば誰もが山行に参加できる点にあるといえる。

とはいえ、そんな御嶽信仰の担い手である「御嶽講」も、もともとは修験道そのものを母体としており、その宗教的儀式は修験道から習い学んできたと考えられる。おそらく山に神や仏を感じ、その地で始まった信仰の原点は修験道であった。

その後の時代の流れの中で江戸時代後期に本格的に始まった「御嶽講」は、母体の信仰形態を保持しながら、修験者という、言うなればプロの宗教者ではなく、俗世間に生きる庶民みずからが登拝や修行、祈祷といった宗教活動の担い手となることで、独自の展開をしてきた。

さらに明治維新後には当時の国家的な宗教政策の影響を多分に受け、各講それぞれに神道的な要素を強く取り入れ、神道の教派神道各教団に変貌を余儀なくされた。その結果、今でも聞こえてくる御嶽教や木曽御嶽本教などの教団を創りあげることとなった。

このように御嶽山は近世から近代にかけての、日本の山岳信仰史や宗教史の大きな転換点を代表する霊山であるといえる。

この木曽の御嶽山をはじめて仰ぎ見た時、誰もがその山容の素晴らしさに感動するに違いない。特に、初夏や初冬のころに山頂の峰々に雪を抱いた姿を見ると神々しいまでに美しく、また裾野に広がる深緑の森林や紅葉の谷などには、季節を問わずその姿のなかに神や仏の存在を感じてしまう。夏の山頂に身を置けば、紺碧の空、雄大な雲に手が届くのではないかと思え、周辺の山々や岩場に咲き誇る高山植物に目を移せば、そこが神や仏のおわす在所であることを実感する。

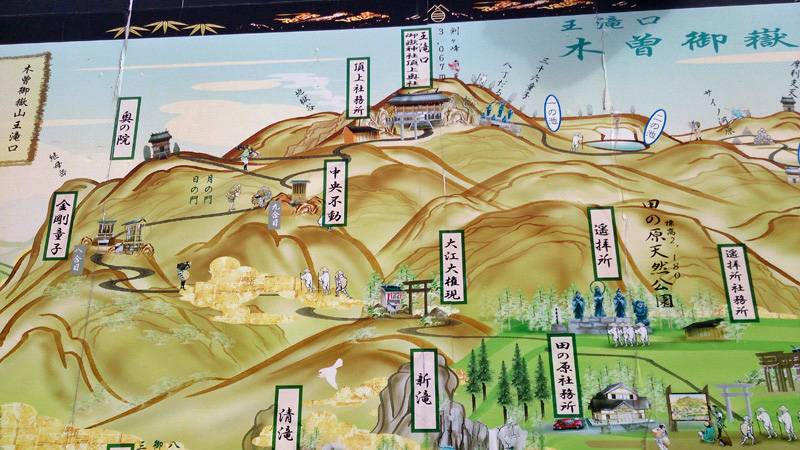

至ってシンプルな神々との交流は、当たり前のように眼前に広がる大自然への感謝と畏怖の心の先にあり、古くは修験道の形態に習いながら、特徴のある信仰の山として歴史を刻んできた。その独自性は、御嶽山麓の各集落、特に黒沢と大滝に鎮座する両御嶽神社を中心とした山への信仰であることや、江戸時代中期に御嶽山信仰を昇華させた中興の祖・覚明行者と普寛行者とその弟子たちへの信仰でもあること、また山頂を守る御嶽大神、山腹の各要所を守る諸神仏、山麓に祀られた諸霊神など山中に祀られた神々が一定の秩序の内に配置されて祀られていることに表れている。

人々はそうした神や仏の存在に導かれ、四季を通じて登拝を行い、その体験がともに登った仲間との信頼関係を作りあげ、信仰を深め、集団登拝の際の結束に重要な役割を担っていると言える。こうした様々な要素が全体として相互に関係しながら御嶽山信仰が成り立ってきた。これらの要素を構成する基本は「大自然と神(仏)と人間」の調和ある関係にほかならない。

僕らは大自然の一部であり分身である。このひとつの小さな命もその他の多くの命に囲まれ、守られることで成長し生きている喜びを得ているものだと思う。大自然だけが特別なものではなく、人間の命すらも大自然の形成要素の重要な存在なのではないだろうか。

自然があり人がいて、それらを繋いでくれる神や仏の存在を感じることができたならば、古くからの信仰が時とともに形を変えたとしても、僕らの心に刻まれた御嶽山という心象風景は薄れることなく後世に繋げていくことが出来るように思えてならない。

*

自身の御嶽山への想いを綴る形でこの記事を書かせていただきました。平成26年の火山災害のなか、御山にて命を全うされた方々とそのご親族や関係者の皆様にとって、つらい思いを振りかえさせることになってしまうのではないかと頭を悩ませました。

同時にこの記事が少しでも故人を偲ぶきっかけになることができたらという勝手な思いのもと、あの火山災害が僕らに教えてくれたことを、僕自身、今後の山とのかかわり合いの中で忘れることなく心に刻んでいきたいと思っています。

※写真は噴火前の様子のものも含まれています

The gods who connect us with nature - Mt. Kiso Ontake (1/2)

Mt. Kiso Ontake is located on the border of Nagano and Gifu prefectures, in roughly the center of the Japanese archipelago. It has long been important to the psychological makeup of the locals, as well as being a historical subject of worship.

Many Japanese people remember the mountain’s eruption in 2014, the worst volcanic disaster since the end of the war. The unexpected news of the massive explosion, which caused many casualties and deaths, left us in shock, horror and despair. It reminded us of the astounding might of nature, easily forgotten during the calm period of a volcano’s apparent dormancy.

Even now in 2019, the mountain (with its continuously-observed small scale belching of volcanic ashes) reminds us to be cautious when visiting its environment. And there are some sections of the mountain that are restricted by local governments.

As with any mountain, when visiting Mt. Kiso Ontake one must prepare as much as possible, never lose humbleness in the presence of nature’s ferocity, and pay the utmost attention to your surroundings at all times.

*

If you climb Mt. Kiso Ontake in the summer, you will come across many people wearing traditional-looking white robes. They’re participating in the “summer mountain climb ritual” organized by groups called “Ontake-kou (御嶽講)”, Ontake pilgrim groups. Sendatsu (先達: holy mountain guides) unite people of all kinds in a single group, where the young and strong will help the aged or infirm. Slowly but steadily, they move together towards the top of the mountain, where the deities await.

On their way, they will stop at various “praying spots (拝所)” to chant Buddhist mantras and make symbolic gestures, like how Buddhist mountaineering ascetics (itinerant monks), the shugenja/yamabushi, do. It’s interesting that, at the same time, they also practice Shinto rituals; clapping, reciting Shinto ritual prayers, and conducting the ceremony called “oza” that invokes deities. Each “kou” (講: pilgrim group) is different in their style, but many Ontake-kou groups continue to honor both Shinto and Buddhist deities and ancestral spirits. These practices are living examples of the syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism.

I mentioned shugenja. These mountain-based monks share the same animist beliefs as the Ontake-kou and sendatsu, and live in the same mountain-worshipping world. And yet, the precise religious faith of each shugenja is different to the next, depending on which mountain they were trained on. Most wear solemn, heavy costumes and run tirelessly around the mountain like gusts of wind, clambering up craggy cliffs and pushing themselves to extreme situations so that they hover between life and death in their training.

Ontake-kou participants, lead by a sendatsu, instead wear simple white attire and travel the mountain paths much more carefully, keeping pace with the slowest person so that everyone gets to the destination together, with no one left behind.

Both the intensely-trained shugenja and the inclusive Ontake-kou see spiritual beings in everything that surrounds them; greenery, flowers, trees, rocks, rivers, the wind, clouds … all of nature and its phenomena. They equally conduct various rituals and prayers from both Shinto and Buddhism.

Shugendo probably came first. Ontake-kou activities and folklore owe a debt to the rituals and practices of the itinerant ascetics, who traveled from afar to the mountain with the conviction that the deity they worshipped, or Buddha himself, was present there. After a long period of local folklore and animism-type mountain-worshipping, pilgrimages to the holy mountain began to be formalized as Ontake-kou in the late Edo period (late 19th century).

Then, Ontake-kou activities were unique in that they weren’t led by “professional” religious practitioners, but by average people who taught themselves the various rituals, prayers and forms of worship (This is still true today).

After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the Japanese government made Shinto the official religion of Japan, strictly banning Buddhism and the syncretization of Shinto with Buddhism. Various kous were forced to institutionalize and become part of denominational Shinto sects, Ontake-kyo and Kiso Ontake Hon-kyo adopting various Shinto elements into their practices. The sacred mountain Mt. Ontake was the staging ground for the local folklore’s transition into a more formal religion.

Mt. Ontake of Kiso looks particularly celestial in early summer and early winter, when the peaks are embraced by white snow. The elegant slopes and the frills at the foot of the mountain hold deep green forests that change color through the seasons. But no matter the season, I feel the presence of deities, Buddha and ancestral spirits there. At the top of the mountain in summer, you feel as if you can reach out and touch the majestic clouds moving in the cerulean sky. You find the peaks of the surrounding mountains in the near distance, and alpine flora are covering the rocky surfaces of the ground at your feet.

These scenes are more than sufficient to remind your senses that here is where holy existence resides. Your blending into nature is the simplest form of interaction with sacred beings, an extension of a deep sense of gratitude and awe towards the nature that spreads its wings in front of you.

There are many mountains in Japan, but this one is particularly unique in several ways. First, it has a history of long being spiritually worshipped, from the time the mountaineering ascetics came to train themselves there. It is unusual for being the site of worship for two ascetic practitioners, who each rejuvenated the reverence of Mt. Ontake in the middle of the Edo Period: Kakumei-gyoja and Fukan-gyoja.

Its uniqueness can be also experienced in the various shrines in each village surrounding the mountain’s skirts, particularly the Ontake-shrines in Kurosawa and Outaki. Various deities, buddhas and divinities are enshrined at various spots on the mountain itself, and their chosen locations carry meaning, a translation of people’s worship and prayers in the three-dimensional space: the whole mountain.

People travel to and between such spots guided by sacred beings, appreciating the natural beauty of seasons together in Ontake-kou pilgrimages. Sharing such an experience, and the challenge of the climb together, nurtures trustful relationships among kou members of different generations and backgrounds, deepening their personal faiths and uniting them. This harmonious relationship mirrors that of the relationship between the worlds of nature, spiritualism and humanity.

We are merely a part of nature, and each of us is a small replica of the whole of nature. Each and every one of our lives is surrounded and protected by countless other lives, each evolving and living on this ground. While we worship nature, we are also a precious, important element of it, and therefore equally worthy of worship.

Circumstances might influence the shapes and outlook of that faith, but as long as nature exists, connected with humanity and the sacred beings around us, we are able to relate the significance of Mt. Ontake, which has and will impact upon the mental panorama of past, current and future generations.

*

I have to admit it wasn’t easy to decide how to introduce this holy mountain. The heart-rending tragedy of its recent past is still fresh in memory. I was not sure if writing about this mountain would be appropriate in light of the 2014 disaster. But, as it remains symbolic of Japan’s history of the deification of nature, I decided with good intentions to still share this story with my dear readers on this 5-year anniversary of the disaster.

I hope that writing about the mountain might serve as a way to show my condolences towards the families of those departed souls who cherished this special mountain. It is my selfish wish, but I would like to always remember what the volcanic disaster taught us.

プロフィール

中村 真

1972年、東京生まれ。雑誌『ecoloco』や書籍『JINJABOOK』などを発行する出版社の代表を務める。現在、イマジン(株)代表として、五感に響く出版・イベント・広告などのプランニングや、社会貢献プログラムなど様々なメディア活動を展開中。

2013年より広島県尾道市に「尾道自由大学」を開校し、校長に就任。学生時代より世界を旅し、外から見ることで日本の魅力に改めて気付き、温泉と神社を巡る日本一周を3度実行。

著書に『JINJA BOOK』、『JINJA TRAVEL BOOK』、『JINJA TRAVEL BOOK2』『日本の神さまと上手に暮らす法』など。

登山者のための神社学

山に登っていると、登山道の途中や山頂に祠を見かけることが多い。これらの祠はいったい何なのだろうか? 神社を巡る日本一周の旅を三度も実行した、中村真氏が、あっと驚く山の神社の話を書き綴る。